Water Famine, Social Injustice, and River Failure

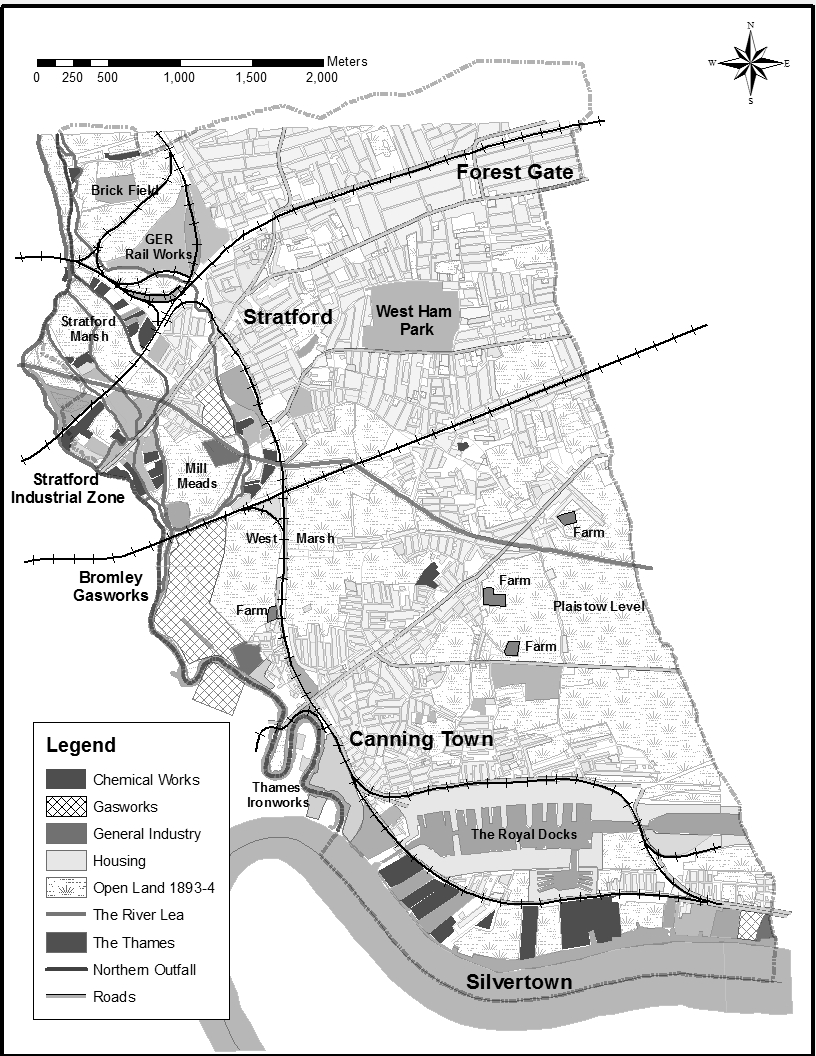

The conservative newspaper, the West Ham Guardian, roundly criticised the East London Waterworks Company (ELWC) for putting dividends before people after it was announced on August 22 of 1898 that West Ham, along with much of East London, was going to face another period of intermittent water supply. The bundle of correspondence kept by the company, together with the local newspapers, make it clear that the majority of the public did not accept that the record low rain fall during the preceding year was the cause of the shortage. Instead the public blamed the monopoly control of the ELWC for not investing the necessary capital to increase the water supply. The population of West Ham had grown by over two hundred thousand people in the past two decades, but there was little reflection on the possibility that the urban growth east of London was overtaxing the capacity of the already strained water supply provided by the Lea. Instead it was seen as another example of the wealthy failing to meet their obligations to the less fortunate. In West Ham the anger that developed as a result of the water famine help unite the electorate behind a socialist led Labour Group in November 1898 elections, resulting in the first labour majority on a municipal council in Britain. This paper will examine the politics of the 1898 water famine within the context of West Ham.