Pessimism and Hope When Teaching Global Environmental History

First published in early June on ActiveHistory.ca

By Jim Clifford

This past year I taught a small but fantastic group of undergraduate students in a course focused on the global environmental history of the industrial revolution. My goal in the course was to situate the massive environmental transformations of the past two centuries in a broad historical context and to provide an opportunity to discuss the benefits and costs of these changes. By the end of the course, however, it became clear that the students recognized the unsustainable nature of the global economy and that they were unconvinced that the more positive and sustainable developments in recent decades would meet the challenge of climate change.

We started the course by exploring global trade and connections from 1400 through to about 1800, recognizing the importance of China and Asia more generally during this time period. From there we explored the ongoing debates about the reasons the industrial revolution started in Britain. With that broad context established we explored some of the environmental consequences of industrialization and globalization over the past two hundred years. This included attention to the colonial disposition, resource depletion and widespread deforestation resulting from the reliance of industrial economies on on raw materials from forests, plantations, mines and guano islands scattered throughout the world. We explored a range of developments with significant environmental consequences, such as the application of industrial technology to fishing and whaling, leading to the collapse of whale populations and once productive fisheries, through to the extractive industries that harvested mahogany, cinchona and gutta percha from tropical forests in South America and South East Asia.

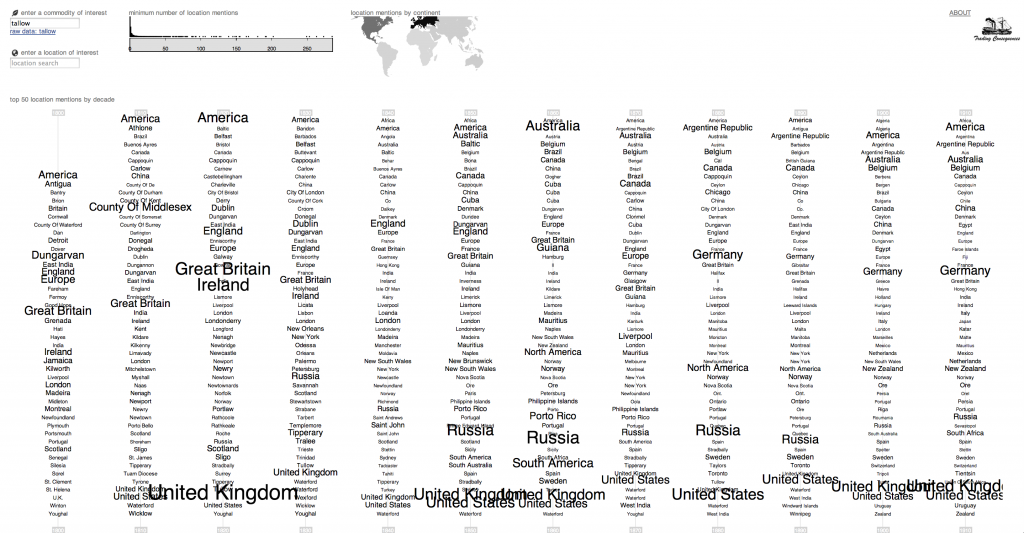

From the Trading Consequences Blog: Today we are delighted to officially announce the launch of Trading Consequences! Over the course of the last two years the

From the Trading Consequences Blog: Today we are delighted to officially announce the launch of Trading Consequences! Over the course of the last two years the

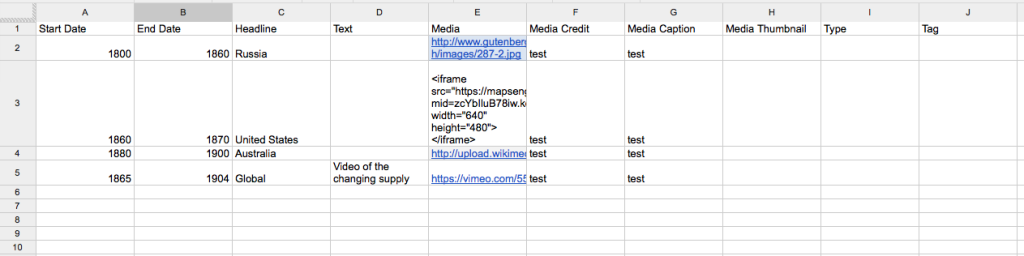

I’ve been a part of a lot of discussions lately about the need for an effective way to share HGIS data. As the number of researchers using GIS for history/historical geography increases, the need to find ways of sharing resources and avoiding duplicated efforts also increases. One way forward is for more of us to post our data on individual websites (see the

I’ve been a part of a lot of discussions lately about the need for an effective way to share HGIS data. As the number of researchers using GIS for history/historical geography increases, the need to find ways of sharing resources and avoiding duplicated efforts also increases. One way forward is for more of us to post our data on individual websites (see the